Simon Hitchens

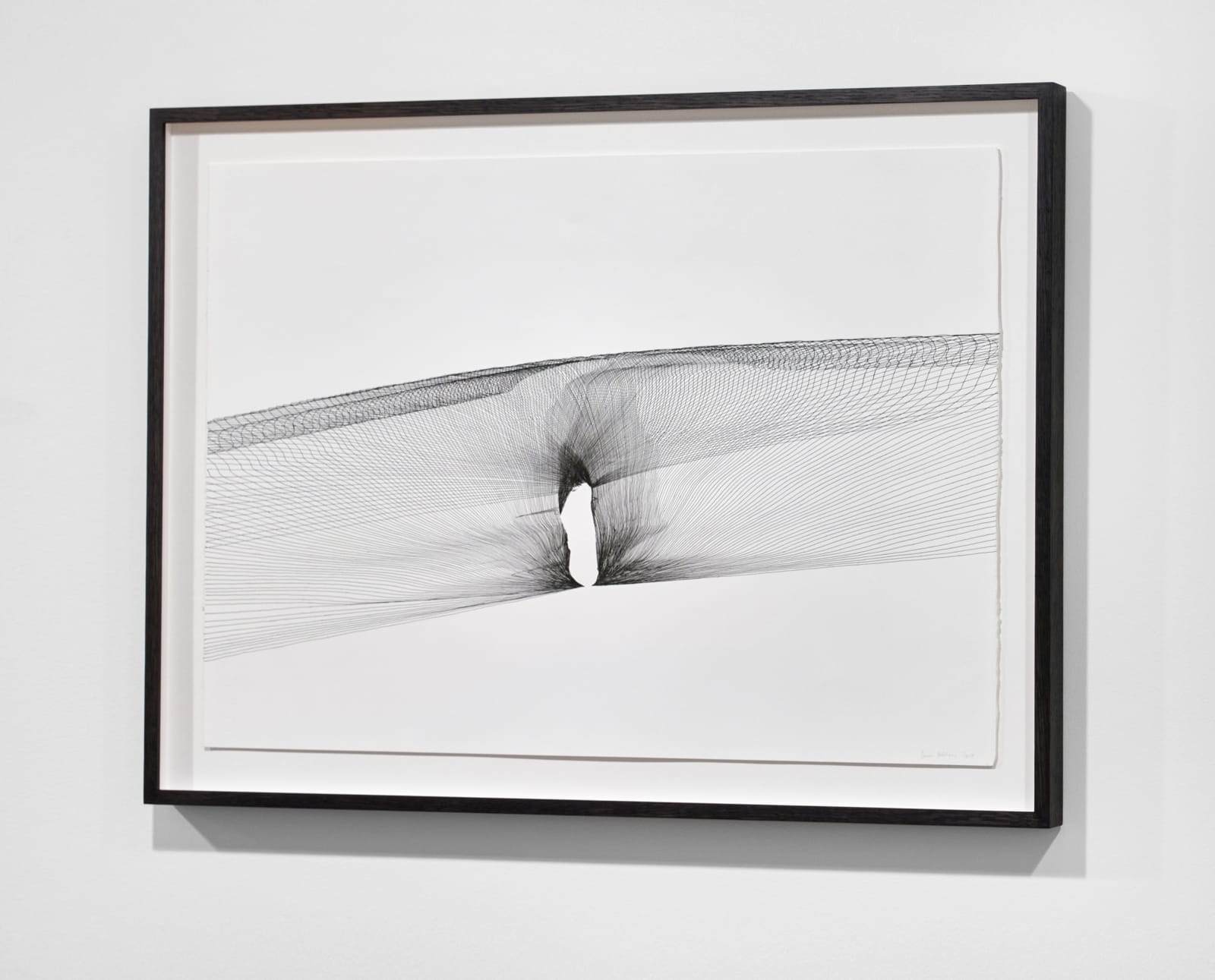

(61.5 x 83 cm framed)

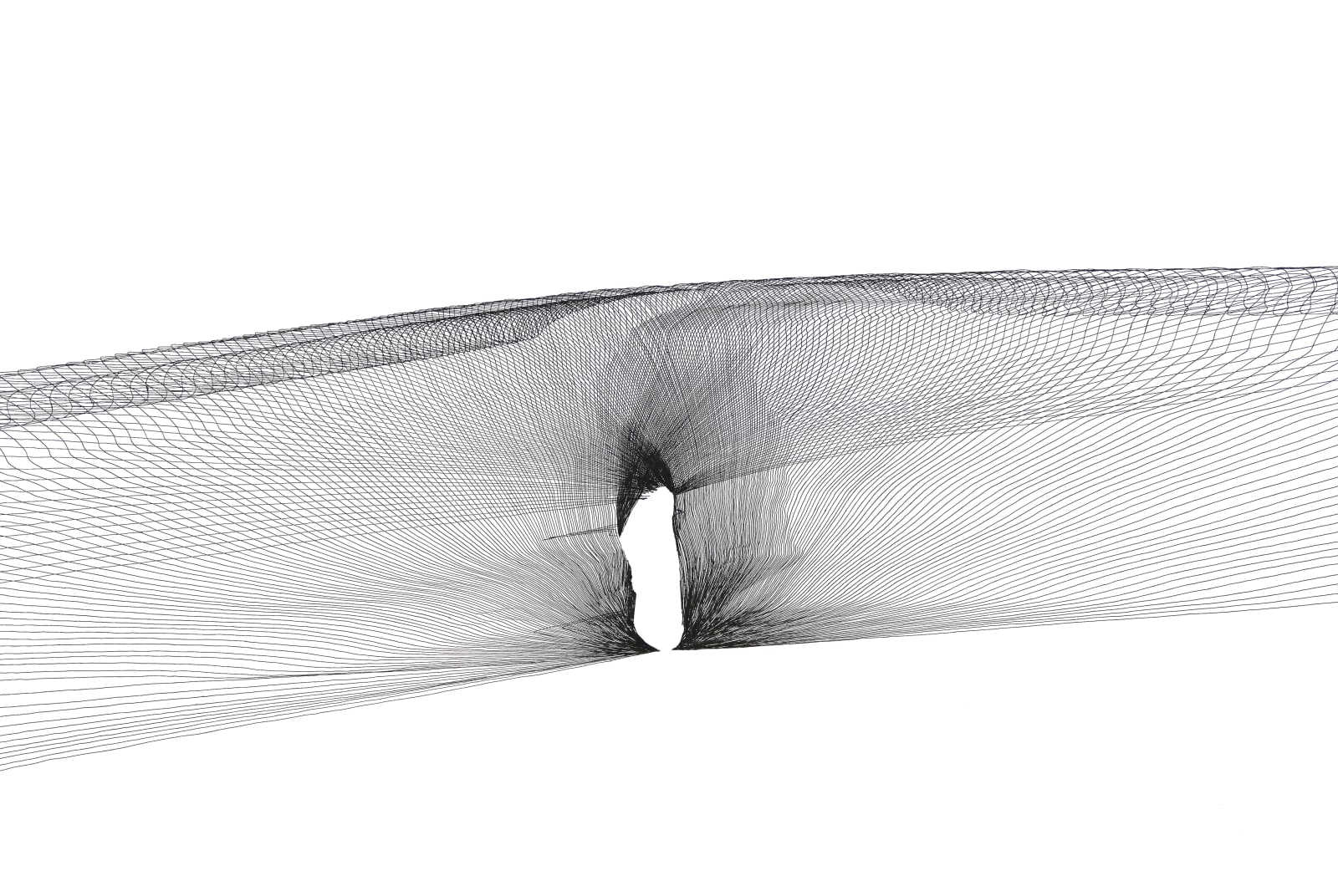

The British Isles have a rich and varied geology, with rocks ageing from the present to some of the oldest on our planet. Each day these rocks get a little older as we too get older. To be able to comprehend the deep-time of rocks is to a shine a light upon our own short lifespan and to begin to understand the transient but interconnected nature of what we share with the world.

For three weeks spanning the autumn equinox of 2019 I travelled the full height of the British Isles, from latitude 50 in Cornwall to latitude 60 in Shetland. The purpose of my journey was to find rocks from eleven different geological time periods and to make a durational day drawing of the shadow lines cast from each rock, on each of the eleven lines of latitude. I would place a rock upon a sheet of paper I had set up before dawn. As the sun rose in the east I would trace its first shadow cast upon the surface of the paper with a pen, taking about two minutes to complete. In that small space of time the Earth had spun just a little on its axis, advancing the shadow and so I would immediately start drawing the new shadow line. This process was repeated relentlessly until either a cloud obscured the sun, and there was no shadow to draw, or the sun dipped below the western horizon at the end of the day. The twelfth drawing is of the youngest geological time period, the Anthropocene; this records the shadows of a discarded lump of plastic drawn upon a landfill site in southern England.

These are process-based drawings made in, of and about the landscape; the result of a particular set of conditions, in a particular place, over a particular span of time. They record celestial time, geological time and human time as well as the weather patterns unique to that day and site: a meditation on time and space. Even the solidity of mountains given time, will eventually erode into nothing, echoing the transience of human life.